China's interest in Belarus looks to be cooling despite its warm words for embattled strongman Alexander Lukashenko, who is attempting to withstand unprecedented protests and intense geopolitical pressure.

Over the past several years, China has emerged as a major patron for the small Eastern European nation of 9.5 million people, lending hundreds of millions of dollars for infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. China also established the Great Stone Industrial Park, a 112-sq.-km business center outside Minsk that has generated $1.2 billion in investments since 2012.

But while the political unrest is pushing Lukashenko to seek closer ties with China, it is forcing Beijing to reassess the depth of its commitment to Belarus, experts say.

"China is one of the few countries to recognize Lukashenko, but it is clear that Beijing has to take account of the risks associated with the situation in Belarus, and that cooperation on a whole series of fronts could become frozen as a result," said Arseny Sivitski, director of the Center for Strategic and Foreign Policy Studies in Minsk.

Lukashenko has ruled Belarus since 1994, earning the nickname "Europe's last dictator" for his autocratic style. Yet following a controversial presidential election on Aug. 9, which he claimed to have won in a landslide, hundreds of thousands of protesters rallied nationwide to challenge the results. Workers at some of the country's largest state-owned enterprises soon joined in, announcing a national strike aimed at financially crippling Lukashenko's government.

Two months later, however, Lukashenko remains firmly in control. Mass protests are still ongoing but most of the opposition's leaders have been either imprisoned or forced abroad. Belarusian security forces have attempted to quell the protests by indiscriminately arresting demonstrators, with reports of torture.

Demonstrators fly the country's old red-and-white flag: The movement and Lukashenko's heavy-handed response have sent a chill through the nation's economy. (Photo by David Saveliev)

"The victims described beatings, prolonged stress positions, electric shocks, and in at least one case, rape, and said they saw other detainees suffer the same or worse abuse," Human Rights Watch said in a report issued last month.

Nikkei Asia spoke with dozens of protesters in Minsk in mid-September, during one of the largest marches in the country's history. They conceded that Lukashenko's violent tactics had a chilling effect on many Belarusians.

"People do not want blood," explained a medical student from Minsk who asked to be identified as Roman for safety reasons. "They realize there is a maniac in power and, if given any reason, he will start spilling a lot of blood."

The wildcat strikes that flared up at several Belarusian factories initially gave protesters hope. But they sputtered after the government fired many workers and closed down some facilities completely.

Lukashenko's crackdown has come at a heavy price for the already struggling Belarusian economy. In just the month of August, Minsk burned through $1.4 billion of its currency reserves amid growing fears that the Belarusian ruble would collapse. "If the [economic] crisis hits, people will resort to hunger riots," said an IT specialist from Brest who asked to be called Vasily. "Lukashenko's only choice is to make the country into a concentration camp where there are slaves and guards."

The president's economic woes are compounded by growing pressure from the West, which he has spent the past several years trying to court. Earlier this month, the European Union, the U.S., the U.K. and Canada imposed sanctions on senior Belarusian officials involved in the post-election clampdown. Over a dozen European nations have refused to recognize Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus.

Lukashenko is still supported by longtime backer Russia, which has just seen another ally -- Kyrgyzstan -- plunge into political chaos over the past week. Last month, the Kremlin pledged to provide Belarus with a $1.5 billion loan. Nearly the entirety of that money, though, will go toward refinancing Minsk's existing debt to Moscow.

Russia has previously made it clear that further economic aid to Belarus is contingent on Lukashenko accepting greater political integration between the two countries -- a prospect he has long resisted.

Feeling increasingly squeezed by the West on one side and Russia on the other, Minsk is turning to Beijing, experts say.

"China is Lukashenko's main hope for surviving in global politics and finding a more decent position for Belarus in it," said Siarhei Bohdan, an analyst at the Minsk-based Ostrogorski Centre.

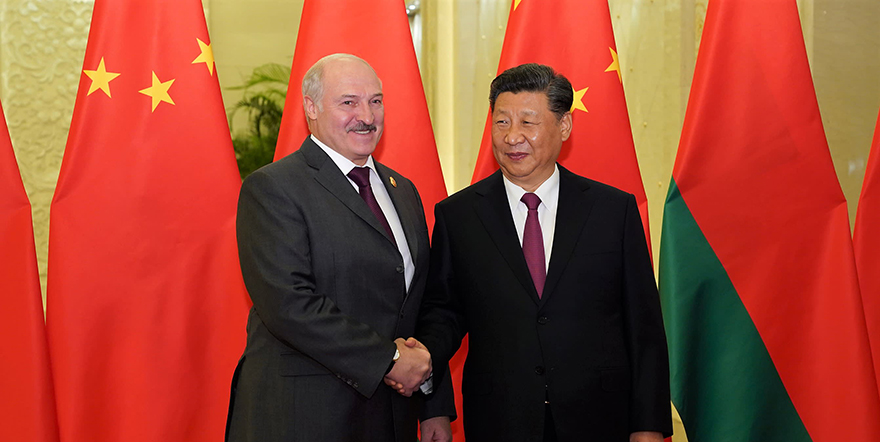

Chinese President Xi Jinping hosts Lukashenko in Beijing in April 2019. © Reuters

Chinese President Xi Jinping was the first foreign leader to congratulate Lukashenko on his "victory" in August's election. Shortly thereafter, the Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a statement condemning "external forces" for interfering in Belarus' domestic affairs and expressed hope "that political stability and social tranquillity will be restored under the leadership of President Lukashenko."

These gestures have not gone unnoticed in Minsk. During a meeting with China's ambassador to Belarus late last month, Lukashenko thanked Xi "for the support he has always provided, especially most recently" and invited the Chinese leader to visit Belarus before the end of the year.

"Tell Xi Jinping that he has reliable friends in Belarus and that Belarus will always be a friendly country for China," Lukashenko said.

Bohdan told Nikkei that Lukashenko hopes to persuade China to expand its production in Belarus, providing the country's struggling economy with much-needed investments. At the same time, the Belarusian strongman wants to gain Chinese military technologies to better deter potential external threats, including Russia. China previously helped Belarus develop its own multiple-launch rocket system, which the country debuted in 2016.

The trouble for Lukashenko may be that he needs China more than China needs him.

Notwithstanding its rhetorical support, Beijing is unlikely to go out of its way to prop up the besieged Belarusian leader, explained Zhang Xin, a research fellow at the Center for Russian Studies at Shanghai's East China Normal University.

China's interests in Belarus "hinge on the country's overall stability rather than a single politician," he said. "So, I highly doubt there will be a dramatic expansion of investments or loans for Belarus just to support Lukashenko as a leader."

Zhang added that there was less funding available for Belt and Road projects due to the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent global economic slowdown, making it even more unlikely that China would provide new major economic assistance to Belarus.

An anti-Lukashenko march in Minsk on Sept. 12: Experts say the political crisis hurts Beijing's plans to use the country as its gateway to Europe. (Photo by David Saveliev)

Perhaps the biggest obstacle to Minsk's desire to expand cooperation with Beijing is, ironically, Lukashenko's growing estrangement from the West.

China has long viewed Belarus as a potential entry point for its goods into the European market due to the country's geographic location. In 2019, over 90% of rail freight traffic between China and Europe went through Belarus, according to Belarusian Railways.

"This political crisis negatively impacts China's plans for transforming Belarus into a regional hub in Eastern Europe and a gateway into the European market," said Sivitski of the Center for Strategic and Foreign Policy Studies.

"Until Belarus normalizes relations with the West, it will be of little interest for major Chinese companies, for whom entering Western markets is the main priority today."

Cover: Reuters