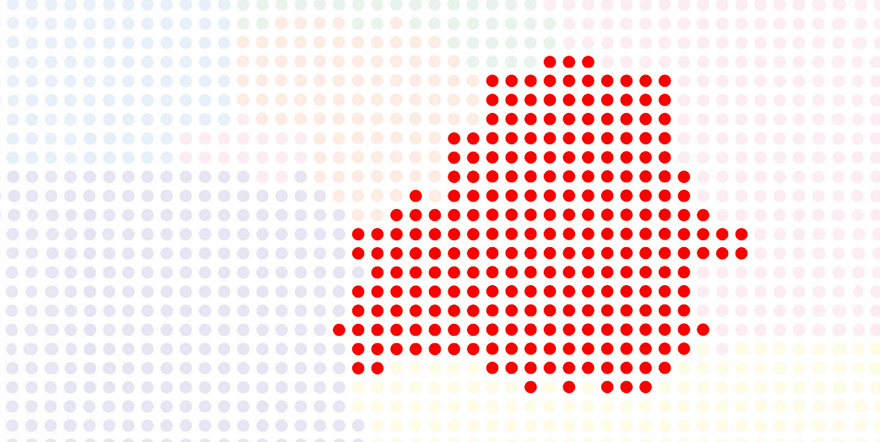

Despite a deep level of political-military integration, Belarus has managed to preserve a considerable degree of strategic autonomy within its alliance with Russia. In 1990s, the Belarusian leadership succeeded in ensuring that the institutional architecture of the joint military components (Regional Group of Forces and Unified Regional Air Defence System) of the Union State were all designed in a way that gives Minsk the option to exercise veto power over any Kremlin decisions inconsistent with Belarus’s national interests (e.g., command and control over joint military components, consensus-based procedure of decision-making). This is one of the main reasons why Belarus never became involved in any recent Russian military adventures, including the war with Georgia (2008), ongoing conflict with Ukraine (since 2014), geopolitical standoff with the West, and other Kremlin-backed crisis around the globe.

Since at least 2015, however, Russia has been demonstrating that it is no longer satisfied with the status quo regarding the military-political integration within the Union State. By pushing a new model of military integration – establishing Russian permanent military presence in Belarus, resubordinating the Regional Group of Forces to the Western Military District of Russia, and creating a single military organization of two countries – the Kremlin tried to shake the constraints to its strategic intentions within this supranational format, namely, Belarus’ considerable veto power and strategic autonomy.

Although the 2020 post-election crisis in Belarus resulted in a significant aggravation of relations with the West and Belarus’s increasing dependence on Russian economic, political, and security assistance, the Belarusian leadership is not going to meet the Kremlin’s strategic demands regarding the deeper political-military integration. However, in need of political and financial support from Moscow, Minsk speculates about its readiness to integrate deeper within the framework of the Union State in the field of security. In fact, A. Lukashenka still resists to establish a Russian permanent military base and is ready to make only tactical concessions to the Kremlin, such as resuming the practice of joint air-patrolling missions and establishing a joint training centre of air force and air-defence forces in Belarus, but under his full command and control and on the rotational basis. Moscow has to content itself with little and agree with these formats, since they also serve the goal of expanding its influence over Belarus and conveying a message to the West and other geopolitical actors that the country is a part of the Russian privileged sphere of influence. Moscow can also justify and present these initiatives in response to the NATO enhanced Forward Presence in the Baltic States and Poland, also on rotational basis.

Nevertheless, since 2014, irreversible processes have been taking place in military cooperation between Russia and Belarus. Russia is reducing its dependence on Belarus for military security in the western strategic direction by deploying and reformatting new groups of troops. And Belarus is losing its exclusive status as an indispensable military partner for Russia, typical of the late 1990s and early 2000s, which was well demonstrated during the Zapad–2021 Joint Strategic Exercise and the delay in the extension of agreements on Russia’s free lease of two military-technical facilities on the Belarusian soil (474th Gantsevichi Independent Radio Technical Site and the 43rd Communications Node of the Russian Navy).

In this context, Belarus’ attitude towards NATO has been dictated by the international security environment and geopolitical conjecture and depending on different phases of five-years domestic political cycle. The 2020 Belarus political crisis has put them at the lowest point. But despite the radical antiWestern and anti-NATO rhetoric of the Belarusian leadership, which is directed primarily at the Kremlin, Minsk is striving to establish pragmatic and mutually beneficial relations with the Alliance, although for ideological and political reasons, all the misfortunes of the Belarusian regime have been blamed on it. It might be an indication that Minsk is preparing ground for resuming its balancing act strategy due to increasing pressure of the Kremlin insisting on its own format and parameters of crisis resolution and power transfer (via a constitutional reform) in Belarus.

However, the prospects for dialogue are complicated by a new model of official Minsk behaviour on the international arena, increasingly associated by Western countries with threats and challenges to regional and, lately, global security (especially after Ryanair aircraft forced landing and use of the migrant crisis to put pressure upon the Baltic states and Poland). Further development of cooperation with the Alliance is also limited by institutional and ideological constraints, which include the lack of necessary NATO framework agreements, false perceptions in the West of Belarus as a political-military appendage of Russia (not without the efforts of the Belarusian authorities themselves), and growing concerns over the human rights situation in Belarus.

Evolution of Belarusian-Russian military cooperation prior to the 2020 post-election crisis in Belarus

Upon coming to power in 1994, President A. Lukashenka almost immediately announced that economic and political-military integration with Russia would be among the strategic priorities for the Belarusian foreign policy. In the mid-1990s, he signed a number of treaties and agreements with Moscow, culminating in the conclusion of the 1999 Treaty on Establishing the Union State of Belarus and Russia and representing a sort of strategic deal between two countries.

The idea for this strategic deal was developed in 1995–1996 in the depths of Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI), an analytical centre subordinated at the time to the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) under Yevgeny Primakov. In its assessments, the Russian intelligence community concluded that Kremlin’s strategy towards Minsk should be guided by geopolitical interests, especially in the military sphere, and not solely economic considerations. It guaranteed Russia’s national security in the western strategic direction, as it could serve as a land corridor to Russian troops in Kaliningrad in case of a hypothetical crisis scenario. In the end, the Kremlin proposed Lukashenka who had faced already a serious economic crisis and isolation from the West to conclude a strategic deal that he gladly accepted.

In accordance with it, Belarus pledged to join the various ongoing integration processes with Russia and agreed to renounce its Euro-Atlantic aspirations – in contrast with a number of other neighbouring post-Soviet states that had already decided to join NATO and the European Union. In light of NATO and the EU’s eastward enlargement as well as the emerging conflicts in North and South Caucasus and Central Asia, Belarus suddenly took on a crucial role for Moscow, ensuring Russia’s national security in the western strategic direction, particularly with respect to the Kaliningrad exclave. In turn, Russia was obliged to provide Belarus with preferential oil and natural gas supplies, offer privileged access for Belarusian industrial and agricultural products to the Russian market and financial assistance, as well as supply the Belarusian military with significantly discounted (if not outright free) arms and equipment. In brief, Russia agreed to exchange economic and military-technical support for a certain level of geopolitical loyalty and security services in the western strategic direction on behalf of Belarus. Thus, security and military integration became one of the cornerstones of this bilateral strategic deal.

In January 1995, Lukashenka signed the Customs Union Agreement with his Russian counterpart, then-President Boris Yeltsin. The two leaders also concluded agreements that allowed Russia to lease for free two Soviet-era military-technical facilities for a 25-year period (expired on June 7, 2021). One of these facilities is the 474th Gantsevichi Independent Radio Technical Site (ORTU) with a stationary digital decimetre radar station (radar) of the Volga type, located near the village of Ozerechye, Kletsk District (48 km southeast of Baranovichi), which is part of the Russian Space Forces Missile Attack Warning System (MEWS). It is designed to detect launches of ballistic missiles and space objects at ranges up to 5000 km in the western sector of 120 degrees, i.e., in Western Europe, the North Atlantic Ocean and the Norwegian sea. Work on building the ORTU began in 1986, but only in the first half of 2002 it was put on pilot combat duty, and October 1, 2003 – on combat duty. The number of Russian service personnel is about 600 people. In addition, up to 200 citizens of Belarus work at various facilities that support ORTU activities.

The second facility is the 43rd Communications Node of the Russian Navy, located 7 km west of Vileika, Minsk region, which was put into service on January 22, 1964. The Antey radio transmitter (RJH69) located at the site ensures continuous radio communication of the Russian Navy Headquarters with the ships and submarines, including those on submarine duty in the waters of the Atlantic, Indian and partly Pacific oceans, as well as radio reconnaissance and electronic warfare, and operates for other branches of the Russian armed forces and service branches: Strategic Missile Forces, Air Forces, Space Forces, etc., transmitting reference time signals as part of the Beta project. The number of personnel at the communications node is about 350 officers and midshipmen of the Russian Navy. The external perimeter of the facility is guarded by freelance personnel from among Belarusian citizens.

In 1995, when signing these agreements, the Kremlin agreed to partially write off Belarus’s debts for energy resources. In addition, Russia was obliged to share with Belarus intelligence data about the regional space and missile operating environment, as well as provide access to training ranges for conducting air-defence combat firing (in particular, at the Ashuluk training ground) due to the absence of such installations in Belarus.

Neither ORTU “Gantsevichi”, nor the 43rd Communication Node are actually military and technical facilities of a foreign state. They are legally the property of Belarus under lease and have no enclave status, so they are not foreign military bases in the legal sense.

Simultaneously, since 1995, the process of developing a system of collective security and military cooperation within the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (in particular, on the issue of a unified air defence system) took place. But these formats didn’t meet Belarus and Russia’s strategic intentions towards each other and were less profound comparing to the bilateral ones.

In January 1998, the Concept of Joint Defence Policy of Belarus and Russia was adopted, defining the main principles and directions of the joint defence policy, common approaches to the organization, and provision of armed defence of the Union of Belarus and Russia against external aggression. According to the document, the purpose of creating the Regional Group of Forces (RGF) is to parry military threats and repulse possible aggression. It was assumed that RGF would take part either in a frontier armed conflict (with the aim to localize and stop such a conflict) or in a similar international conflict (with the aim to repel aggression, to defeat coalitions of aggressor’s troops and create conditions for termination of military actions on favourable conditions for the member-states of the Union of Belarus and Russia).

The deployment of RGF is carried out during the threatened period (period of growing threat of aggression) by decision of the Supreme Council of the Union of Belarus and Russia (that is, by joint decision of the heads of state). In addition, during the threat period, the Joint Command of the RGF is created on the basis of the Ministry of Defence of Belarus. In practical terms, this means that the position of RGF commander is permanent (non-rotational) and always occupied by the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Belarus (since March 2021 – General Major Victor Gulevich).

Until then, the associations, formations, military units and institutions of the Armed Forces and other military formations of Belarus and Russia, allocated as part of the RGF, remain directly subordinated to their respective national ministries and commands. Planning for use of the RGF is carried out by the respective national General Staffs. The RGF is responsible for the socalled region – territory of Belarus and the neighbouring regions of Russia (which, therefore, excludes Kaliningrad region).

In October 1998, an agreement was adopted between the Belarus and Russia on joint use of military infrastructure facilities in the interests of national security. According to the document, the defence ministries of the two countries are developing a list of military infrastructure facilities for joint use in the interests of the RGF. During peacetime, troops are let through to these facilities by prior agreement between the authorized bodies, in wartime – in accordance with the RGF deployment and application plan. The sides also undertake to preserve and develop these facilities.

The Treaty on the Creation of the Union State of Belarus and Russia, signed in 1999, fixed the functioning of RGF in the exclusive competence of the Union State. However, since all key decisions on this issue are made by the Supreme State Council of the Union State (i.e., by presidents of the two countries on the basis of consensus), this provision has changed little in terms of RGF command and control.

Today, the RGF consists of all ground and special operations units of the Belarusian Armed Forces as well as the 1st Guards Tank Army (military unit 73621, Moscow region, Bakovka) of the Russian Western Military District. The 1st Guards Tank Army was established in 2014 and substituted the 20th Combined Arms Army (military unit 89425, Voronezh) as part of the RGF after the latter was deployed on the border with Ukraine to assist Kremlin-backed separatists in the military conflict in Donbas.

The 2001 Military Doctrine of the Union State enshrines the principle of collective defence: the member-states of the Union State regard an attack on one of them as an attack on the Union State as a whole.8 However, in order to declare an act of aggression against the Union State, a Supreme State Council must be convened and a corresponding consensus decision of the heads of states must be taken. Without this decision, the RGF application plans cannot be automatically activated.

The 2009 Agreement between the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation on joint protection of the external border of the Union State in the 73 airspace and creation of the Unified Regional Air Defence System (URADS) of Belarus and Russia was the next step in the development of BelarusianRussian military integration. However, it came into force only in 2013, due to prolonged political wrangling by the two sides. Unlike the RGF, which carries out strategic deployment only in a threatened period, the URADS exists and functions on a permanent basis in peacetime. A commander of the URADS is appointed by joint decision of the presidents of Belarus and Russia.9 However, since the URADS was created back in 2013, only Belarusian representatives have been put in charge of it — Air Forces and Air-Defence Forces Commanders of the Republic of Belarus Oleg Dvigalev (2013–2017) and Igor Golub (since 2018). This fact is quite remarkable, demonstrating Belarus’s strong desire to preserve control over this joint military component.

In peacetime the ministries of defence of the two countries together with the commander of the URADS plan the use of troops (forces) and means of the URADS and organize their air defence combat duty and interaction. Direct subordination to the national commands is preserved. During the threatened period, the URADS becomes a composite part of the RGF and operates according to a single plan, and a Joint Command is established.

Today, the URADS includes all Air Forces and Air-Defence Forces of the Belarusian Army as well as the 6th Air Forces and Air-Defence Forces Army, located on the territory of the Western Military District of the Russian Federation (military unit 09436, St. Petersburg).

In 2016–2017, a package of updated documents regulating the activities of the RGF was adopted. In 2016: the Directive of the Supreme State Council of the Union State on joint actions; the Plan of Operations of the RGF of the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation; the Regulation on the Joint Command of the RGF of the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation; the Structure of the Joint Command of the RGF and URADS of the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation. All the mentioned documents have been classified. In addition, a new Military Doctrine of the Union State is being developed. In 2017, the Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Belarus and the Government of the Russian Federation on joint technical support of the RGF was adopted. According to this Agreement, Moscow is legally constrained in when it can deploy military assets across the border to Belarus, nor is there any pre-deployed Russian military equipment in Belarusian storages. Namely, the Russian Ministry of Defence is allowed to transfer and deploy to Belarus all necessary military equipment and weapons 74 for the 1st Guards Tank Army and the 6th Air Forces and Air-Defence Forces Army only in the period of a growing military threat (threatened period) to the Union State and in wartime. The material and technical base of the Armed Forces of Belarus is used jointly in this case.

However, the need to adopt the updated documents was caused by organizational and staff changes in the national formations of the armed forces of Belarus and Russia, assigned to the RGF and URADS, as well as clarification of the subordination of the URADS in relation to the RGF. They did not essentially change the decision-making and command-and-control of the RGF and URADS, but merged them in one entity – the Regional Group of Forces consisting of the land and air components.

Thus, although a strategic military and political ally of Russia, Belarus wields enough checks and balances to block any unilateral decision by Moscow and preserve a high degree of strategic autonomy within their joint alliance. It is based on the fact the Belarusian side controls permanently the positions of the RGF Commander, URADS Commander at the current stage of the rotation, while all political and military decisions within the Union State including application of the RGF and URADS are taken and approved by the Supreme State Council, the main collective decision-making body, on the basis of consensus by leaderships of Russia and Belarus.

Military cooperation between Belarus and Russia in the post crisis period: follow the deeds, not words

The political crisis that erupted after the August 2020 Belarusian presidential elections sharply affected Belarus’s modus operandi on the international arena, removing the association with its contribution to security and stability in Central and Eastern Europe of the 2014–2020 period. The crisis significantly aggravated Belarus’s relations with the West and led to an increasing dependence on Russian economic, political, and security assistance. No surprise, the Kremlin has been exploiting Belarus’s return to isolation from its Western partners and Lukashenka’s pro-Russian rhetoric in order to expand its influence over the vulnerable ally. For political and ideological reasons, the sides pretend in public that there are no serious contradictions between the countries, and that the process of integration, including in the military sphere, is developing systematically. But by demonstrating geopolitical loyalty to the Kremlin in the form of tactical concessions related to military cooperation, Lukashenka is trying to sideline the Kremlin’s agenda of deeper politicalmilitary integration, establishing a permanent military presence in Belarus, as well as dictating the scenario of power transfer through a constitutional reform on the Russian terms as a way to resolve Belarus political crisis. In practice, despite the statements of the Russian and Belarusian leaders about breakthrough agreements concerning the development of a common defence space of Russia and Belarus, they remain far from being consistent with each other’s strategic interests and demands.

Since at least 2015, however, Russia has been demonstrating that it is no longer satisfied with the status quo regarding the Union State. Namely, by preserving its considerable veto power and strategic autonomy within this supranational format, Belarus actually constrains the Kremlin’s strategic intentions. The constraints come from not allowing Russian permanent military bases on its soil as well as abstaining from involvement in Russia’s conflict with Ukraine and confrontation with the West.

In addition to the Kremlin’s unsuccessful attempt to push the issue of a Russian military airbase in Belarus14, in September 2015, the commander of the troops of Russia’s Western Military District, Anatoly Sidorov, proposed to include the joint Regional Group of Forces within the structure of the group of forces in the Western strategic direction. In other words, he effectively proposed reassigning the Armed Forces of Belarus, which are part of the RGF, to the command of the Russian Western Military District (Joint Strategic Command “West”). It is worth pointing that that, in 2016, the Kremlin implemented this model in its relations with Armenia. The Russian-Armenian Joint Group of Forces (JGF) is included in and assigned to the Southern Military District (Joint Strategic Command “South”). The commander of the Southern Military District can exercise command and control over the JGF in a period of growing military threat (threatened period).

At the end of 2015, Russian Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu proposed to complete the formation of a joint military organization of the Union State by 2018.17 This proposal referred to an in-depth integration of the military and security apparatuses of Belarus and Russia, with a joint decision-making centre in the Kremlin. Such a model has already been implemented with regards to Russia’s military relations with the separatist (and Moscow-backed) Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Altogether, the above-mentioned Russian proposals to Belarus demonstrate that Moscow no longer considers Minsk an equal partner from a formally institutional point of view and intends to reshape their militarypolitical alliance by undermining Belarus’s strategic autonomy. While the Belarusian leadership has the opposite intentions – to preserve the strategic autonomy and veto power within the joint military alliance with Russia, as well as monopoly on the use of force in the country. The change in this status quo risks the loss of power by A. Lukashenka.

These conflicting intentions have been reflected in the recent joint military initiatives – resuming joint air-patrol and air defence missions and establishing three joint combat training centres. The first initiative is stipulated by the Action Plan for on-duty air-defence forces within the framework of the URADS agreed upon at the end of 2020. The second initiative is envisaged by the bilateral Strategic Partnership Program for 2021–2025 signed between ministries of defence in March 2021. One of these joint facilities, a joint combat training centre of the Air Force and Air-Defence Forces, is located on the territory of Belarus, in Grodno and Brest region. Russia will host the other two combat training centres — in Nizhny Novgorod (for motorized rifle and tank units) and Kaliningrad oblasts (for naval infantry and special operation forces).

On September 9, 2021, the joint units took on combat duty to jointly protect the airspace of the Union State of Belarus and Russia, at the 61st Fighter Air Base of the Belarusian Air Forces (military unit 54804), in Baranovichi, Brest region. At the same time, joint air-defence units in the western part of Belarus assumed combat duty with the same tasks. The purpose of the Joint AirDefence and Air Force Training and Combat Centre is to improve professional instruction and study new types of equipment that, in the near future, may be put into service in the Belarusian army. Moreover, the centre will improve the practical skills of personnel from the Armed Forces of Belarus and the Russian Aerospace Forces.

Russia contributed both air-defence and air force components to this facility. On August 28, the first train loaded with Russian military equipment and crews — including multifunctional radars, command-and-control vehicles and at least two S-400 surface-to-air missile (SAM) launchers — arrived in Grodno, Belarus. Presumably this equipment is from the 210th Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment of the 4th Air-Defence Division of the 1st Army of the Air- and Missile-Defence Forces. The S-400 units brought into Belarus were deployed on the territory of the 2285th Independent Radio Technical Battalion, near the positions of the 1st Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment of the Belarusian AirDefence Forces, equipped with S-300PS SAMs, in Grodno region, only four kilometres from the Polish border.

On September 8, 2021, at least a wing of four Russian Su-30SM heavy fighter jets landed at the 61st Fighter Air Base in Baranovichi, Brest region,22 where they will stay to conduct both joint training and combat duty missions. Presumably, they belong to the 14th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment of the 105th Combined Aviation Division of the 6th Air Force and Air-Defence Army of the Western Military District of Russia.

Belarusian military officials argue that the Joint Training and Combat Centre strengthens the practical component of the Unified Regional AirDefence System (URADS) of the Union State, meaning the facility is presumably included in this system as a subordinated element. According to the agreement on the joint protection of external borders that established the Union State URADS, peacetime duty by joint assets and crews is carried out in accordance with the duty plan approved by the Russian and Belarusian ministries of defence. Russian aircrews on combat duty in Belarusian airspace are put in the air by an agreed decision of operational duty officer of the Control Centre of the Aerospace Forces of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation and the operational duty officer of the Central Command Post of the Air Force and Air-Defence Forces of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Belarus. The procedure for the use of weapons and military equipment by forces on air-defence duty is determined by the legislation of the party on whose territory the weapons and military equipment are used. In sum, this means that, legally, all Russian military assets and crews assigned to the Joint Air-Defence and Air Force Training and Combat Centre in Grodno are subordinated to the Belarusian side – i.e., the Central Command Post of the Belarusian Air Force and Air-Defence Forces.

And if political and geopolitical expediency prompts Belarusian leadership to withdraw the visiting Russian forces back to Russia, it will take this step. Illustratively, A. Lukashenka ousted four Russian Su-27PM fighter jets in 2015, fulfilling the same tasks of joint air-patrol missions the previous time, against the backdrop of the escalating Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

Therefore, the Joint Centre in Grodno and Brest regions should not be seen as a Russian “military base” in terms of command and control since it lacks extraterritorial status and does not subordinate directly to Russian command. It is worth noting that the Kremlin specifically tried to dictate those terms and conditions in 2015, when it unsuccessfully pushed for installing a Russian airbase in Bobruisk, Belarus.

By subscribing to the idea of a joint training centre on Belarusian territory, Lukashenka apparently tried to secure the inflow of modern Russian military equipment (at least eight Su-30SM fighter jets and one S-400 SAM battery with Russian crews) for free and under his command. He also tried to substitute the Kremlin’s agenda of establishing a Russian military base in Belarus by making tactical concessions in the form of Russian limited and rotational military presence. But it seems the Kremlin saw through his cunning plan and provided him with only four Su-30SMs and two S-400 SAM launchers, most likely on a rotational basis. The Russian leadership still considers a permanent military base in Belarus as the only acceptable option despite Lukashenka’s constant arguments that there is no military-strategic necessity for such a step. Therefore, Moscow is not interested in reinforcing the Belarusian Armed Forces by supplying extensive modern Russian military equipment for free or even on preferential terms. From the geopolitical point of view, stationing troops on the ground is the most effective means of securing Belarus within the Russian sphere of influence. Therefore, it is highly unlikely Moscow will ever accept Lukashenka’s arguments as to why a permanent Russian base is unnecessary – particularly amidst his vulnerability at home and isolation from the West. But at this particular moment the Kremlin is satisfied even with the rotational military presence in Belarus – it conveys a message to the West and other geopolitical actors that Belarus is a part of Russian privileged sphere of influence. Moscow can also justify and present these initiatives in response to the NATO enhanced Forward Presence in Baltic states and Poland, also on rotational basis.

The quadrennial Russian-Belarusian Joint Strategic Exercise Zapad–2021, held on September 10–16, 2021, didn’t reveal any substantial changes in command and control of the joint military components as well as decisionmaking algorithms, at least when it comes to the Belarusian part of the exercise, that should be distinguished from the Zapad-2021 Strategic Command and Staff Manoeuvres of the Russian Armed Forces.

The scenario of the Joint Strategic Exercise Zapad–2021 largely reflected the propaganda narratives of the Belarusian authorities, which they used to describe the events of the political crisis in Belarus in August–September 2020, rather than real strategic concerns. Back then, according to the Belarusian authorities, the Western countries, including the US, Poland and Lithuania (in the exercise scenario these were codenamed as “Westerns” – Pomoria, Nyaris, the Polar Republic), sought to implement a scenario of regime change in Belarus, annex the Grodno region (one of the most protested regions, where local authorities went to meet some of the protesters’ demands), break Belarus away from Russia, and undermine the unity of the Union State (in the exercise scenario these were codenamed as “Northerns” – the Republic of Polesye and the Central Federation) to create a territorial base for hybrid aggression against Russia.

The exercise scenario envisaged an escalation of local conflict to the level of the regional war after the failed coup attempt and hybrid aggression. So, the “Westerns” began launching precision-guided missile strikes against critical infrastructure in Belarus and preparing a coalition group of forces to conduct offensive invasion operation. While the URADS was repelling precision-guided missile strikes, the Russian part of the RGF was deploying in the Belarusian territory. After that, the “Northerns” first were defending, and then turned to counterattack in order to complete the defeat of the adversary and restore the lost positions.

It is true that the descriptive part of the exercise scenario stipulated not only the formation of the RGF by Armed Forces of Belarus and the 1st Guards Tank Army and the 6th Air Forces and Air-Defence Forces Army of the Western Military District (in the scenario, the 11th Tank Army and Air-Space forces grouping), but also the deployment of the 20th Combined Arms Army of the Western Military District (in the scenario, the 51st Army) of Russia in Belarus, as well as probably the 41st Combined Arms Army of the Central Military District as a reserve (in the scenario, the 30th Army) deployed close to the Ukrainian border during escalation of military tensions in Spring 2021. However, this description also reflects propaganda narratives of the Belarusian leadership, repeatedly stating that the entire Western Military District (WMD) will help to defend Belarus in case of a military aggression rather than illustrates organizational and staff changes in the RGF. In particular, this is evidenced by the participation in the territory of Belarus of units only from the 1st Guards Tank Army of the WMD of Russia (4th Tank Division and 2nd Motorized Rifle Division). At the same time, the composition of RGF could be reenforced by including in it the 76th Airborne Assault Division of the Russian Armed Forces, that actively took part in the exercise. Some other Russian units deployed close to the Belarusian border could be assigned to the RGF (for instance, the 144th Motor Rifle Division of the 20th Combined Arms Army of the Western Military District located in, Yelnya, Smolensk Region). Thus, there are no signs that the RGF might have resubordinated and included in the Western Military District in accordance with the Kremlin’s intention of 2015.

In general, the beginning of the conflict and its further development in the exercise scenario reflected the understanding by Belarusian and Russian military strategists not only of the concepts of hybrid warfare, but also of the so-called multi-domain battle developed by the US’ Department of Defence.

At the same time, in contrast to the previous period, the current Zapad–2021 Strategic Command and Staff Manoeuvres of the Russian Armed Forces overshadowed the Zapad–2021 Joint Strategic Exercise, turning it from a landmark bilateral event in Belarusian-Russian military cooperation into a multinational event, in which Belarus is only one of a dozen participants, albeit the second most important. This serves as more evidence of the Kremlin’s intention at depriving the Belarusian-Russian relations of the exclusive status in the field of military security. Minsk is shifting to the level of one of Russia’s peripheral partners in this area, the importance of which is determined by the specific situation in the region. This knocks out the historically most effective and, in fact, the last argument of influencing the Kremlin position towards Minsk from the Belarusian leadership, nullifying the strategic significance of Belarus for Russia. While before 2021, the Belarusian authorities were emphasizing that Belarus was protecting Russia in the Western Strategic Direction, the current Zapad–2021 exercise reveals that it is no longer the case, and Russia is now pretending to become a security provider for Belarus.

By September 30, 2021, all Russian units that had participated in the Zapad-2021 Joint Strategic Exercise withdrew from Belarus. And only a wing (of four) of Su-30SM fighters and units of the S-400 complex assigned by the Russian side to the Joint Training and Combat Centre for of the Air Force and Air Defence Forces remained on the territory of Belarus.

The ongoing negotiations over extending the free lease agreements on the 474th Gantsevichi Independent Radio Technical Site and the 43rd Communications Node of the Russian Navy after the June 2021 deadline expired also reflects the contradictory nature of the bilateral relationship. More recently, Russia deployed analogous facilities on its own territory and the two installations on Belarusian soil no longer hold any major militarytechnical significance, but it is the only available form of Russian military long- term and permanent presence in Belarus. In its turn, the Belarusian leadership is trying to conclude a package deal exchanging its approval for preferential supplies of Russian modern military equipment to Belarusian Armed Forces. However, it is still unclear whether the Kremlin is going to meet Lukashenka’s demands and accept this package deal.

NATO in Belarus’s Threat Perception: From a Partner to the Root of All Evil and Vice Versa?

Belarus’s attitude towards NATO has been dictated by the international security environment and geopolitical conjecture, and has depended on different phases of five-years domestic political cycle. Traditionally, the lowest point in the relations with the Alliance coincides with the beginning of a new five-years domestic political cycle in Belarus, immediately after the presidential elections that traditionally face harsh criticism of the West and subsequent sanction pressure due to human rights violations and mass repressions by the Belarusian authorities (with the exception of the 2015 presidential elections).

But when the Belarusian leadership is concerned about Russia’s pressure and interference in the domestic affairs of the country, Minsk tries to establish pragmatic and beneficial relations with NATO in order to counterbalance the Kremlin’s strategic intentions. It was the case in 2008–2010 and 2014–2020, when A. Lukashenka was pushed by Moscow to support Russia’s military aggression against its neighbours. Moscow urged him to recognize the independence of Georgian separatist regions South Ossetia and Abkhazia, as well as join the Kremlin’s military campaign against Ukraine and subsequent geopolitical confrontation with the West, including the deployment of a Russian military base in Belarus allegedly in response to the NATO enhanced Forward Presence in Baltic states and Poland.

When Belarus was associated with a regional stability and security provider in 2014–2020, Belarusian leadership wanted to expand constructive dialogue with NATO on the basis of trust, equality, transparency, and mutual respect. A. Lukashenka also believed at the time that warmer relations with the Alliance would eventually enhance the security of Belarus. The idea to upgrade relations with NATO was natural, considering that Belarus shares a border with three NATO member states (Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia) and Ukraine, which intends to join the Alliance in the future. According to Lukashenka, neither Belarus nor its neighbours needed dividing lines; therefore, Belarus and NATO should be actively talking to each other.

The 2020 Belarus political crisis has reversed these intentions, at least on the level of official rhetoric. In response to non-recognition of Lukashenka’s legitimacy and sanction pressure by the West, the Belarusian leadership accused the EU, the US and NATO of waging a hybrid war against Belarus and exporting a colour revolution to the country, including attempts of invading Belarus by NATO forces at the call of the Belarusian opposition. Moreover, Lukashenka weaponized his anti-NATO rhetoric, speculating on Russia’s strategic phobias. According to him, if the revolution had been successful, NATO would have placed its troops close to Smolensk, transforming Belarus into a springboard for an attack on Russia. By deploying such rhetoric, the Belarusian leadership not only solidarized with the Russian anti-NATO propaganda, but also wanted to mobilize the Kremlin’s support, emphasizing that Belarus still defends Russia, and limiting freedom of the Kremlin’s actions on the Belarusian track.

According to the Belarusian military officials, over the past few years, NATO forward command centres have been established near the western borders of the Union State of Belarus and Russia. Implementation of the US “Four Thirties” initiative, adopted at the 2018 NATO Summit, will enable NATO to expeditiously concentrate a much more considerable ground force near the Belarusian borders.

Belarusian military authorities believe that operational equipment of the territories of Belarus’s neighbouring countries is being actively upgraded, including special warehouse facilities for accommodation and maintenance of weapons, military and special equipment, storage of materiel stocks, and storage of ammunition in the interests of the US Armed Forces. NATO exercises are conducted with high intensity in the vicinity of the state border of the Republic of Belarus, during which, among other things, the issues of troop redeployment, preparation of advance routes and areas of combat mission, creation of groupings, setting up crossings, forcing water obstacles, landing troops and many other tasks specific to offensive operations are practiced. At the same time, the Belarusian General Staff considers conducting exercises to be one of the main elements in training of troops. However, the nature and progressing intensity of such exercises cannot but cause concern, especially after a series of provocative actions on the part of Belarus’s Western neighbours.

Such rhetoric is traditionally aimed at demonstrating geopolitical loyalty to Russia, it serves propaganda purposes of official Minsk rather than reflects the real threat perception. In fact, despite the crisis in relations with the West, Belarus seeks to build equal dialogue with NATO, increase openness and develop mutual understanding as part of strengthening international and regional security. These agenda points come from the priorities of the planning cycle of cooperation between NATO and Belarus within the framework of Partnership for Peace (PfP) program for 2022–2023.

Belarusian military officials consider the development of dialogue with NATO as one of important areas in ensuring national and regional security. From this perspective, the NATO PfP program is a tool for maintaining and strengthening, for mutual benefit, cooperation in the political, military, economic, scientific and legal fields with the Alliance as a whole, as well as with NATO member states and partner countries separately.

Officially, participation in the PfP Planning and Review Process (PARP) is consistent with the Belarus’s policy of openness and transparency in the field of defence and military planning. The implementation of the partnership objectives within the PARP allows to work towards achieving interoperability of forces and means, allocated from the Armed Forces of the Republic of Belarus and the Ministry of Emergencies of the Republic of Belarus, with forces and means of NATO to participate in joint activities of operational and combat training, as well as activities to maintain international peace and security under the aegis of international organizations.

Belarus has established a national legislative basis for participation in activities to maintain international peace and security, and there is interest in practical participation in NATO exercises, as well as in the framework of the PfP. Also, Belarus is intending to:

- continue the work under the provisions of the Agreement between the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Belarus and the NATO Cataloguing Committee on the provision of services for connection to the NATO cataloguing system, signed in 2016;

- complete the interagency internal consultations conducted in preparation for accession to the Agreement between the member states of the North Atlantic Treaty and other states taking part in the Partnership for Peace on the status of their forces of June 19, 1995, and the Additional Protocol thereto;

- continue consultations with the relevant structures of NATO and individual member states of the Alliance to complete the process of certification of the Security (Information) Agreement, in order to expand the list of promising areas of cooperation both with NATO in general and with individual member states of the Alliance in particular.

Such messages might serve an indication that Minsk is preparing ground for resuming its balancing act strategy due to increasing pressure of the Kremlin insisting on its own format and parameters of crisis resolution and power transfer (via a constitutional reform) in Belarus.

However, today the main obstacle in development of relations between NATO and Belarus is the political crisis in the country and its international implications. Further development of cooperation with the Alliance is also limited by institutional and ideological constraints, which include the lack of necessary NATO framework agreements, and false perceptions of Belarus as a political-military appendage of Russia (not without the efforts of the Belarusian authorities themselves) in the West. Growing concerns over the human rights situation in Belarus and the lack of progress in democratic reforms will be a deterrent factor as well.

The prospects for dialogue are also complicated by a new model of behaviour of official Minsk on the international arena. With the beginning of the political crisis in Belarus after the August 2020 presidential election, the actions of the Belarusian authorities are increasingly associated by Western countries with threats and challenges to regional and, lately, global security (especially after Ryanair aircraft forced landing and use of the migrant crisis to put pressure upon the Baltic states and Poland). The Belarusian side has found itself in a position when the strategy of converting its contribution to regional stability and security into various political-economic and diplomatic dividends from the West no longer works because of the harsh reaction to the results of the presidential campaign and large-scale repressions against civil society, bringing the human rights and democracy agenda back to the first place in relations with Minsk.